2 months ago, someone reached out to us to build a Voice Agent to handle all inbound calls to their business. They kept missing these calls and were flustered about leaving money on the table. They were a digital marketing agency staffed by only 2 employees and were mainly providing services to chiropractors.

Out of curiosity, I asked them: “How many calls are you receiving per day?”. There was a moment of reflection, after which they replied: “We get around 1-2 calls per week”.

Sir, you don’t need a Voice Agent for that. Your time and attention is better spent elsewhere. The world is filled to the brim with untested advice and puffery advertising. Whatever convinced you that you must adopt AI did not reveal the entire picture.

Nothing gets us into greater trouble than our belief in untested advice; our habit of thinking that what others think as good must be good; believing counterfeits as being truly good; and living our life not by reason, but by imitating others.

So, is AI useless?

There’s an interesting phenomenon that occurs in cultures and markets and has been well described in behavioral science. People tend to converge to an extreme position around a certain topic and later on when reality proves to be different, they immediately lurch towards its antithesis.

Artificial Intelligence is going through a similar transition, based on signals such as Karpathy’s podcast with Dwarkesh, Ilya’s declaration that LLM scaling is dead, renowned researches claiming they’re sick of transformers and AGI predictions not panning out.

Daniel is an ex-OpenAI researcher.

Markets are spooked and sentiment around AI is rapidly turning sour. I’m seeing people shift from wanting AI everywhere to wanting AI nowhere. Heck, I can’t even count the number of articles I’ve read this past week with titles such as “No, we don’t want your cool AI”.

This type of Groupthink is just as lame as when people were deifying AI. We are simply going through a trough of disillusionment, making us think there’s nothing positive in AI when that’s obviously not the case. Take the following examples.

Software engineers’ entire workflows have changed. No one is writing code the same way it was written in the pre-LLM era. In fact, if AI-enabled coding is done right, engineers are 10-30% more efficient on average.

Personal injury law firms are deploying AI to categorize and summarize large document sets and to surface insights from similar cases undertaken in the past.

Chauffeur services companies are introducing automation to their booking processes to ensure new booking requests are taken care of without delays.

Retail, media, logistics, healthcare and others have figured out and invested in a variety of industry-specific use cases for automation.

While as much as 95% of investment probably went into unsound use cases for AI, a good chunk of that was because the hype machine charmed the pants off executives and decision-makers, not because AI in and of itself is useless.

Where to begin automating?

I’ve wasted considerable time scouring the internet in hopes of finding actionable playbooks on automation but all I have ever discovered are vapid articles like this and this. Anything valuable is either locked up behind a paywall or in a consultant’s mind somewhere.

Since I’ve found myself in the consultant role quite a few times this year, I have crafted a simple, “don’t beat around the bush” framework of my own that I turn to when conducting discovery with our clients. Here is the 30,000-ft view.

The bush

The entire $200B consulting industry suffers from an ailment: generalization. Problems represented and thought about in their general forms are much harder to solve but that’s precisely what consultants do when they obnoxiously talk about their models and frameworks. So I’ll try to be different: I’ll explain my framework by walking through a specific example, that of a law firm.

Rote tasks

Jobs are a collection of discrete tasks and these tasks are varied in their nature and dynamism. Some of these discrete tasks may be wholly or partially automatable while others should stay a mile away from any AI. Therefore, to reason about worthwhile automation, the first step is enumerating all the distinct tasks that make up a job role.

For example, a database from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics lists ~22 tasks that a lawyer undertakes as part of their work. I’ll list some of them down below.

Prepare, draft, and review legal documents

Negotiate contractual agreements

Gather evidence to formulate defense or to initiate legal actions

Perform administrative and management functions related to the practice of law

These are bad examples because they’re still somewhat generic but that’s as much specificity as you can expect from a public database built off of surveys. In reality, you’ll have to go deeper. Instead of saying “Performing administrative tasks”, you may have to say:

Entering daily time entries with task descriptions

Reviewing and editing pre-bills before sending to clients

Submitting expense reports to Clio for firm expenditures on behalf of a client

Renaming, versioning and organizing files within the firm’s DMS

Logging all communications and associated files (such as email attachments) into the practice software

Managing client intake i.e. creating matter records, running conflict search, sending client intake forms, tracking engagement letters etc.

Fill in all repetitive e-filing form fields

Despite what the world may tell you, job-level automation is not a foreseeable reality today forcing us to step down one level below and think in terms of tasks. Another factor to consider is which job role you pick to analyze.

For example, all executive consultants I’ve run into get a little uncomfortable when I ask them: so what does your day-to-day look like? It may in part be because many of them are charlatans but even the ones worth their salt get uncomfortable at that question. That’s because they don’t have a neatly defined day-to-day, making it especially cumbersome to mine rote tasks out of a usual day in their life. You’ll want to avoid beginning with such job roles.

Become a grader

The next step is somewhat mechanical and involves grading each task on four metrics: Verifiability, Volume, Data Availability, Risk.

Here, you’ll use a mix of quantitative data (for example, looking at the total number of time entries per lawyer per day in your practice software to assess Volume) and qualitative judgments (for example, assessing how easy it is to Verify the correctness of a created time entry).

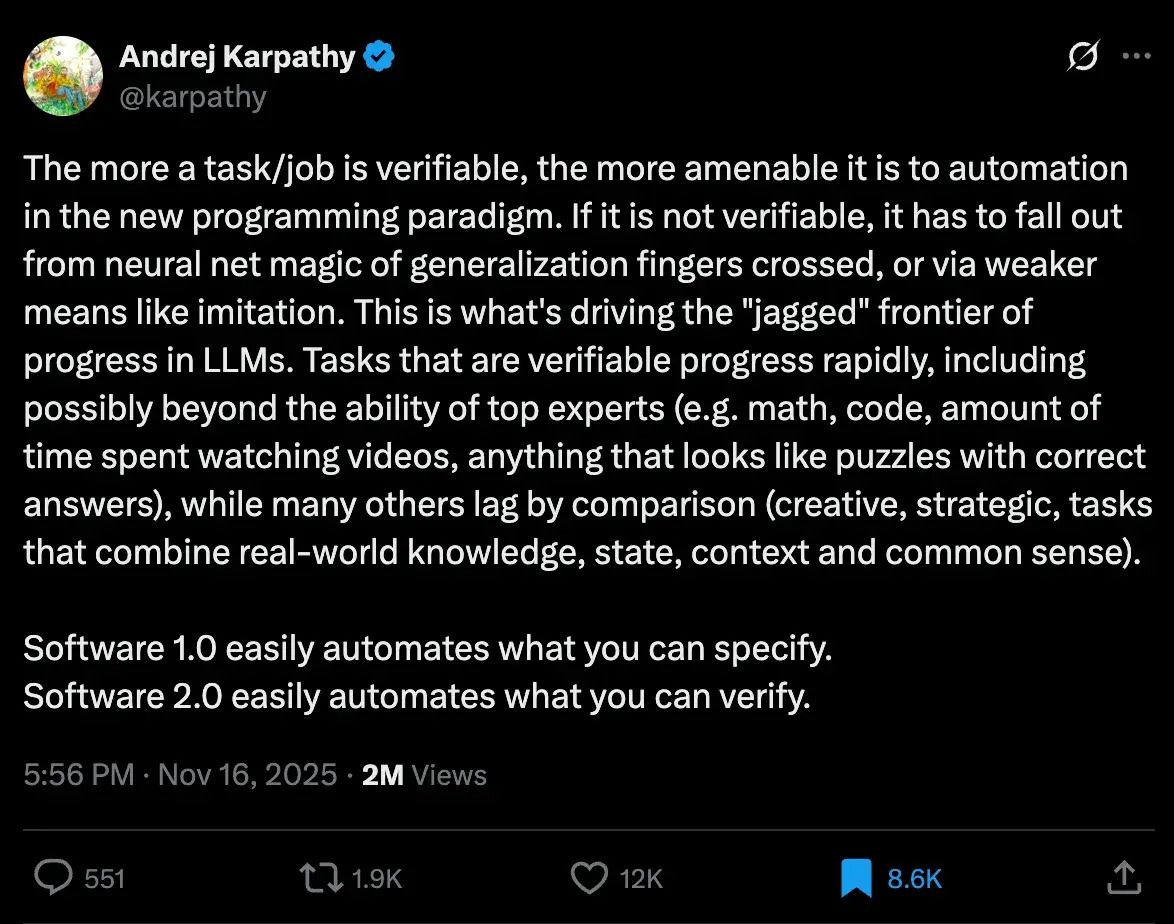

The king of all metrics is Verifiability i.e. if a task were to be automated, in part or wholly, can the output be quickly verified, without having to do the task again or expend a lot of effort (relatively speaking)? The higher a task scores on Verifiability, the more amenable it is to automation. Karpathy does a better job of explaining this than I ever could.

Software 2.0 easily automates what you can verify.

Volume is funny to write about because it is an idea adjacent to the idea of automation and all of us instinctively know that automation is very rarely going to be worth it for a one-off event. In fact, what pushed automation into vogue was the Industrial Revolution in an attempt to mass produce goods. “Producing goods” was a task that had to happen as many times a day as possible and was considered the only task worth automating, for a time.

If a rote task happens once a week and takes up 30 minutes per instance, it will be scored low for Volume. If it occurs many times a day and takes up 2 minutes per instance, it will be scored high for Volume. This reflects the principle that when assessing Volume, frequency of the task takes a higher priority than the average time taken to finish it. Additionally, the longer it takes to finish a task, the less likely it is to be handled reliable by current AI capabilites.The third metric (Data Availability) may not always be relevant because of LLMs. LLMs have already been firehosed with internet-scale data and as a result, have acquired quite a lot of general patterns. If the rote task at hand is robotic and common, chances are that a model out there already has the “world knowledge” required to perform it. In such cases, you would grade Data Availability as high as possible.

Conversely, if performing the task requires specialized knowledge not available to the internet (generation of RFP responses to sell your company’s solutions, or handling non-trivial customer support tickets etc.), then Data Availability sticks out like a blot on the landscape. Without high quality data available, you would need to either produce it first (which itself requires a level of data maturity most SMBs don’t have) or abandon automating the task entirely.

Meme applies if your Data Availability score is low, which is not the same as having limited data.

The last thing to be mindful of is the cost of error discovery i.e. Risk. Since modern automation projects lean on LLMs in some way and because LLMs are statistical parrots likely to hallucinate, there will always be a chance that an automated task’s output is invalid. When this happens, we don’t want to end up in a situation where lives are lost, licenses are revoked, professionals are sanctioned, or revenue dips. Here is an excerpt from Professor Ethan Mollick’s newsletter talking about when not to automate (i.e. Risk is too high).

When very high accuracy is required. The problem with AI errors, the infamous hallucinations, is that, because of how LLMs work, the errors are going to be very plausible. Hallucinations are therefore very hard to spot, and research suggests that people don’t even try, “falling asleep at the wheel” and not paying attention. Hallucinations can be reduced, but not eliminated. (However, many tasks in the real world are tolerant of error - humans make mistakes, too - and it may be that AI is less error-prone than humans in certain cases)

Let’s now grade (on a scale of 1 to 10) all the tasks on our list on each of the four metrics. (Actual score may vary from firm to firm based on their practice area).

(Higher scores for Verifiability, Volume & Data Availability mean that the task is more amenable to automation. A high Risk score means the task should not be automated).

Task | Verifiability | Volume | Data Availability | Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Timekeeping | 9 | 10 | 10 | 3 |

Pre-bill reviews | 6 | 3 | 6 | 7 |

Expense reports | 8 | 6 | 10 | 6 |

Document organization | 10 | 9 | 8 | 2 |

Communications logs | 9 | 10 | 10 | 1 |

Client intake | 8 | 6 | 7 | 5 |

E-filing | 10 | 8 | 6 | 8 |

Pass the verdict

Now each task needs to be assigned one of the following labels.

Prioritize now

Prioritize later

Drop

I’ve tried passing the scores through multiple weighted functions to calculate these labels but a mathematical approach here creates a false sense of objectivity for what is ultimately a subjective decision. I’ve found the following heuristics to be more useful instead (follow these unless the context suggests otherwise).

If Risk is high (> 6), label the task Drop.

If Data Availability is low (< 6), label it Prioritize later. Once you’ve better data, you can revisit this task.

For the remaining tasks, sum the Verifiability and Volume scores. If the combined score is high (> 14), label it Prioritize now.

If the combined score is low (< 8), label in Drop. Anything falling in the middle should be labelled Prioritize later.

Applying these heuristics to our law firm example, we get:

Task | Verdict |

|---|---|

Timekeeping | Prioritize now |

Pre-bill reviews | Drop |

Expense reports | Prioritize later |

Document organization | Prioritize now |

Communications logs | Prioritize now |

Client intake | Prioritize later |

E-filing | Drop |

You now have a clear list of automation priorities, marking the end of this post.

Next step is to start building out these automation systems, which comes with its own set of afflictions and pains. But that is something I’ll refrain from talking about in this issue.

Adios.

A note before you go

I’ve tried my best to present an actionable playbook on getting started with automation but it is by no means a transformation strategy, or a strategy at all. It is merely concerned with immediately available initiatives to boost productivity without getting bogged down in consulting speak. That said, if you’re big enough to go the whole nine yards, you should work on your broader AI transformation in parallel.